Published in October 2009

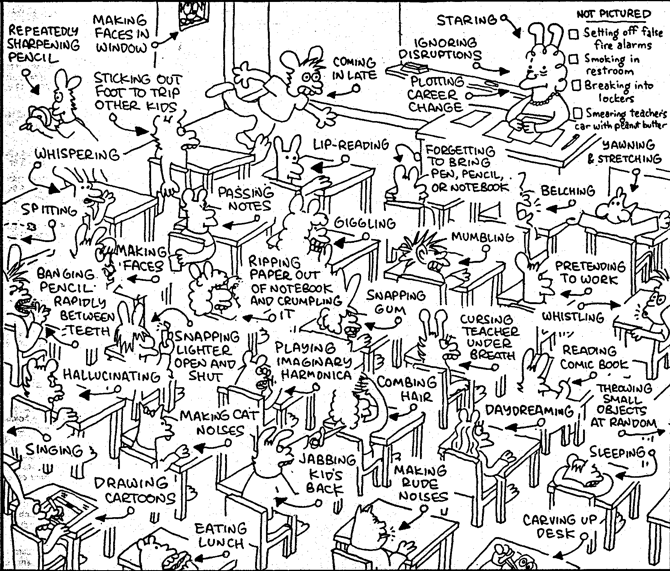

Image source: School Is Hell – Matt Groening

This is the first post with a particular theme in the series “Why is everyone an expert on education?”. The series is written collaboratively by Ira Socol, Dr Greg Thompson and Tomaz Lasic.

Science is an awesome, admirable pursuit of measurable, testable, replicable truth. It is a pursuit of certainty that something has, does and will work as we imagine it. We want to be certain that a medicine we give to our child has been tested and declared safe, a bridge we drive across stable enough to carry us. Data and methods we use give us control to predict, improve, avoid. That’s all fine when dealing with inanimate objects. Yet ask an engineer and they will tell you that even concrete and steel could behave unpredictably, hence the overdesign and consideration of safety margins. Enter humans.

Data and scientific methods give us the delirious joy of thinking that things are repeatable and replicable with human beings too. Because something works/does not work in one context, we assume that that must be the case for all contexts. This applies to curriculum, to standards, to teaching strategies, to discipline and management strategies, to educational psychology, to the very organisation of schooling.

Scientifically observing and measuring actors in schools fools us into believing we are capable of absolute knowledge, absolute categories, and once we got those right – absolute solutions. Fools us? Just look at performance pay for teachers debate, curriculum wars, ad absurdum arguments over accuracy of assessment, validity and usefulness of standardised, statewide literacy and numeracy testing and more. In all these we want to measure so we can be ‘certain’, to establish norms and through them (as the term suggests) normalise people and put them in brackets. Once they are in boxes, brackets and percentages, we can apply the right dose of whatever it is we have come up with as the solution.

Now please – categorisation is a perfectly human thing and helps us live our daily lives, no doubt. But when categorisation becomes unexamined, unquestioned purpose of what we do with human beings in education, then we have a few problems. Or put bluntly: It is rubbish, and it bewilders and alienates students (and with it many teachers, parents and others).

When seeing education as a science, we tend to break it down to its elements, particularly those we are familiar with. Instead of having a more holistic view of an actor in the process of schooling, we prefer a cleaner, reductionist, building-block view. We build walls around and guard our areas of expertise. There we propose solutions to fix things we are certain of. And when we want to justify, we look for figures. In this need, the efficient simplicity of “68% on the test” becomes very seductive. We are insecure in trusting the ‘soft’, slippery immeasurables like intuition, freedom or hope etc. so we invent ever more complex, ‘hard’ systems of quantifying people to cling to and value: “Is this a 72% or 74% answer?” Sounds like “is this Class B or Class C concrete”? But hey, “it has worked for me at school so why not for these kids too, they should be motivated by it.”

So, apart from all having a lot to say and guard as ‘experts’ – where does this lead us?

The problem with education as a science is amplified by the centralised nature of most school systems, where control is exerted from a distance. If you remove relationships from schooling (let’s face it, the majority of system administrators/policy makers spend very little time dealing with relationships in schools), what is left is the idea that schools are largely the same, and therefore, the same tests should elicit the same responses. If they don’t there must be something wrong – and the finger is normally pointed at teachers!

In Australia, USA at least, and we imagine many other countries, the people making decisions on education have probably not done more than tour a school in the last twenty years, yet they still are able to provide ‘expert’ commentary. A few problems rise immediately from this.

First is the modernist view of scientific solution – a belief in the inevitability of human progress through science. These decision-makers enter the debate with a belief that each adaptation in the educational system has been “progressive,” and thus that the education system which they succeeded in was “near perfect” – the result of centuries of continuous improvement. A bit of “tinkering” (Tyack & Cuban, Tyack & Hansot) will thus result in “perfection.” Their authority flows from certainty and the promise of being led to such perfection. The second problem is the idea that success is quantifiable and that the idea of it applies to all of us equally. The third problem is the leaders presuming that their framing of experiences is both correct and applicable universally.

This all adds up to create an understanding of education as a science where results are replicable and reliable. We call this phenomena “white coat replicability”. Governments, the media, and bureaucracies deal in white coat replicability when they talk about effective schools and teachers, about ranking schools based largely on benchmark testing.We are hearing a lot in the media at the moment about Joel Klein and New York public schools. Consider this article which talks about the ways that data collected can be misused and misrepresented.

Today, schools are dominated by externally developed testing, reporting on student achievement that uses mandatory standards and systems, and continual reform. What is this doing to students? Do we think that schools cater more or less for student difference and uniqueness now than they used to? After years of education as a science, the system is at least as discriminatory as ever. We think that we collect and control so much information now, it is slowly paralysing us from dealing in intangibles such as freedom and hope.

The interaction between students and teachers is becoming less relational and more normalised, where outputs are measured and teachers and students are measured and measure each other. The problem with this is that the measurement fixes students as good/bad, successful/unsuccessful, likeable/unlikeable and students increasingly live/perform these measurements. Ever wonder why there are groups of students who are Rebels in every school regardless of context? Schools need rebels to show students who not to be.

This fixing of students into neat packages are things that schools do all the time. After all you can measure deviance/compliance can’t you? Students find these packages very hard to change. We are indebted to the work of Stephen Ball from the University of London and the notion of performativity.

To put it simply, students and teachers are trapped in their performances as a result of the ways they are measured and organised within education as a science. The trick of performativity seems to be that individuals come to see themselves in terms of the data collected. They perform as they feel they should be expected to/come to expect themselves. For example, a “dumb” student may hardly try to do well in a test because he does not see himself smart – and the grades simply confirm it. The data assigns the well-known and well-rehearsed roles. These roles are so reified by repetition that even altering the performance to accommodate (a change in) their self-image becomes unacceptable, much like when one actor discomforts audiences if he/she replaces another in a television series. When students act out of their accepted role (for example, “good” girls getting drunk), they experience negative feedback, often from students as well as teachers. Ontologically, schools teach students to limit their being – limit who they are and can be. Change anyone?

You can’t collect all this data and employ these evaluators in schools without people performing their results (positionality). Want to know why many students feel alienated from schools? One of the key factors is that they are continually judged as being less or even non-successful. The same is true for teachers! Who hasn’t felt despondent when the school they are working in has performed at unacceptable levels in their subject through something like NAPLAN (Australia’s nationwide literacy and numeracy testing)? One of our colleagues had this experience and the school spent the next 6 months ‘diagnosing’ the problem, counselling the subject teachers, exhorting the students to do more, aim higher etc. The end result? Teachers were forced to run after school study classes, they began to ‘teach for the test’ and the school results stayed the same. The drop in teacher morale was curiously never measured, or seen as significant. We don’t think that the educational experiences of the students would have improved as a result either – teaching for the test negates most of what is wonderful in the relationships between teachers and students and the richness of student learning.

So what is being learnt when education is run and organised as a science? That your performances measure you – that you are quantifiable. You learn how to see yourself as a particular type of student/teacher, and grow to see this as ‘normal’ – the business of schools becomes normative measuring and pedagogy becomes sterile, limited, controlling and superficial. But gee it looks clean!